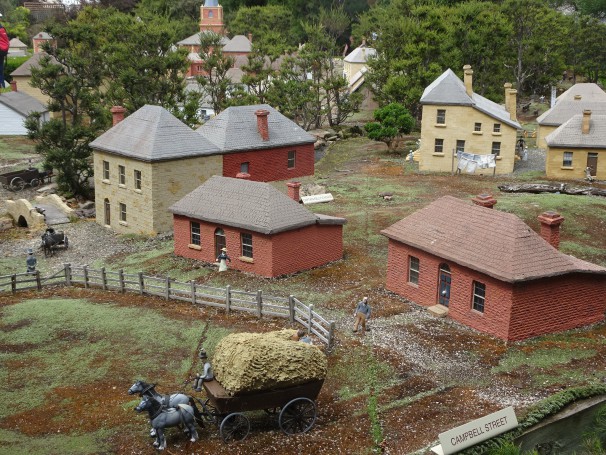

Richmond. Hobart Town model miniature village from 1820s. Campbell Street in the early days.

54432969219_17862c3119_k

Route Richmond-Hobart

6092841130_1845d1b477_h

Route Richmond-Hobart

6092301825_fae1b33725_h

Route Richmond-Hobart

6092841652_586a2eedd5_h

Richmond. Hobart Town model village from 1820s. Warehouses on Hunter Island which is now Hunter Street.

54433152585_d3576a9373_k

Ricmond Tasmania. Wooden residence from circa 1830s now antique shop.

Richmond, Old Hobart Town village and the Pooseum.

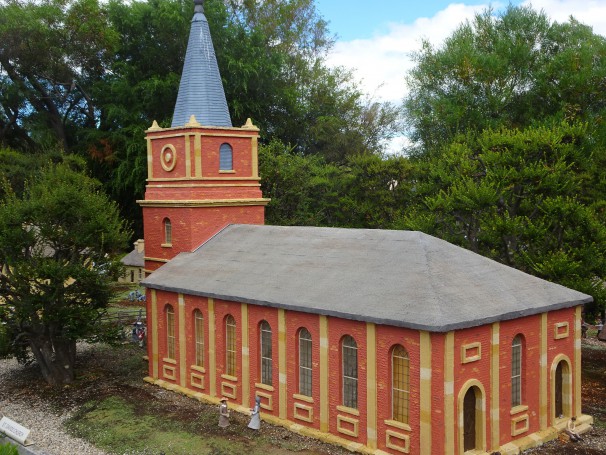

Just a short distance from Hobart is historic Richmond, home to Australia’s oldest bridge. The Coal River which flows through the town was named and discovered in 1803 not long after the Risdon Cove Hobart settlement began. Coal was discovered along the river banks hence the name. The government granted land to encourage farmers to the district and the town of Richmond was declared in 1824 by Lieutenant Governor William Sorrell. It was the gateway to the East Coast of VDL but also a police outpost with a Courthouse, Gaol, and barracks for soldiers and a watch house. An historic town like Richmond with buildings from the 1830s and 1840s is a testament to the role of convicts in building structures in Australia. Government work gangs of convicts built government and public structures such as the Richmond Bridge, the Courthouse, the Gaol etc but assigned convicts with skills would also have helped build some early structures including private houses for their masters. However, we have no records of this. The Richmond Bridge was built by convicts between 1823-25 and is still in daily use. Nearby is Australia’s oldest gaol built in 1825-28. The town grew quickly in the 1830s with much trade between it and Hobart. It is recorded that convicts built St Luke’s Anglican Church, (1834-36) a structure designed by architect John Lee Archer and opened by Governor Arthur. It is the church with the distinctive square tower and no spire. James Thompson the convict in charge of the interior wood work of the church was granted his freedom for his work. Note that the clock in St Luke’s tower came from the original St David’s church in Hobart when it was demolished in 1868 to make way for the Cathedral. The clock was made in 1828 and still keeps perfect time. The Catholic Church was not built by convicts as it was not the Anglican Church of the government. St John’s Catholic Church is the oldest Catholic Church in Australia and was built in 1836. The spire was added in the early 1900s. It also has an unusual side stone turret which houses the pre-cut stone stairs that give access to the gallery. The spire was added to St John’s in 1859 and was replaced again in 1972.

The heritage classified town has many fine Georgian buildings, antique shops and good cafes, 1830s cottages and grander houses. Look out for Oak Lodge in Bridge Street a gentleman’s two storey residence constructed between 1831-42. The bridge was used for all traffic to the east coast (and later to Port Arthur) and by 1830 Richmond was the third largest town in VDL. Wander down to the Coal River and walk under Richmond Bridge. The Richmond Court House was built in 1825-26 by convicts as was the Gaol nearby. Richmond Gaol was designed by Tasmanian architect John Lee Archer and erected by convicts as was the norm for government structures. The gaoler’s house was also designed by John Lee Archer. This complex is the oldest penal set up in Tasmania. In 1826 a group of Aborigines were believed to be attacking and raiding farms. Consequently a group of soldiers on a retribution search attacked and killed 14 Aboriginal people. Six were captured and taken to Richmond Gaol. They were subsequently released as there was no evidence that charges could be laid against them. Such victimisation was not uncommon in those days. Today Richmond relies on tourism and is the base for the Old Hobart Town model village and the scientific based Pooseum- the only one in the world established by an Austrian lady.

Some buildings to look for in Richmond starting in Bridge Street.

•On the corner of Henry St – Ashmore coffee shop. A two storey corner store circa 1850.

•LaFayette Galleries and shop – a fine Georgian style building. Built as a single storey Post Office c 1826. Opposite in old c1840 cottage is the Woodcraft Shop. And next to it is the stone Congregational Church built in 1873.

•The Regional Hotel – a typical 1880s Australian pub.

•On the corner of Edward St the old Saddlery. Originally a general store. Built around 1850.

•Next to it is the Bridge Inn licensed in 1834. Upper floor added in 1860s or so.

•Next to it is the Richmond Town Hall. Built in 1908 with stone from the flour mill and police barracks.

•Next to it is the Courthouse. Built by convicts in 1825. Used as Richmond Council Chambers 1861 to 1933.

•As the street bends on the north side is the old bakery c1830 now antiques shop and next to it some old cottages c1840.

•Opposite the cottages is Mill Cottage built around 1850.

•At the end of the street where the triangular park begins veer right to the Richmond Bridge 1823-25. You can walk down to the Coal River beneath the bridge.

•First over the bridge is Mill House as the water mill was on the river. Built in 1850. C1900 it became a butter factory.

•Turn left here into St Johns Court. It takes you to St John’s Catholic Church and spire.

Retrace your steps across the river and along Bridge Street to Edward St. by the old saddlery.

Edward Street.

•At the first intersection on the left is Ochil Cottage built c1840. Behind it down the side street is the Goal built 1825/28.

•Across the intersection the little cottage on left was a morgue and dispensary.

•Next left in Palladian style with a central two storey section is the Anglican Rectory. Built in 1831 for the town magistrate. Was only the Anglican Rectory 1908 to 1972.

•Next to it is St Luke’s Anglican Church built 1834/36. Built by convicts.

Retrace your steps to Bridge Street but detour right to 22 Bathurst St for a fine little cottage built circa 1830 with dormer windows. If you want to see more 1830s and 1840s houses walk down Commercial Street for one block only. It starts at the Ashmore coffee shop. Commercial St also has the Richmond Hotel, a fine Georgian two storey hotel built c1830.

Richmond. Hobart Town model miniature village from 1820s. Warehouses on Hunter Island which is now Hunter Street.

Overview of Tasmanian history. Early Exploration.

Abel Jansz Tasman of the Dutch East India Company discovered Tasmania in 1642 and named the island after Antony Diemen, Governor of the Dutch East India Company. Van Diemen’s Land was next sighted by the French Captain, du Fresne in 1772 just two years after Cook had sighted the east coast of Australia. Just 16 years later the British settled at Botany Bay and to deter further French exploration and possible settlement on Van Diemen’s Land they established an outpost of NSW on the island in the 1803. Prior to this, explorers like Captain Bligh in 1792 had sighted and named Mt Wellington and George Bass and Matthew Flinders circumnavigated the island in 1798. David Collins began the first island settlement in 1803 at Risdon, but moved it to Sullivan’s Cove in 1804(the wharf area of Hobart). Also in 1804, a northern settlement began at what is now George Town under the control of Colonel Paterson. Paterson moved this settlement to Launceston in 1806. In was not until 1812 that Governor Macquarie acted to bring all Van Diemen Land settlements under the control of Hobart Town. The settlements became semi-independent of NSW in 1825 when Van Diemen’s Land was allowed its own judiciary and Governor.

What happened to the Aborigines of Tasmania?

During the last Ice Age, New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania were joined as one land mass as sea levels were lower. During this cold period (about 35,000 years ago) Aborigines settled lowland parts of Tasmania. As the world warmed, sea levels dropped and about 12,000 years ago Aboriginal groups were left isolated on Tasmania. When whites began settlement of Tasmania there were 9 tribes on the island compromising between 4,000 and 10,000 Aboriginal people. Conflict between British settlers and military and the Aborigines began almost straight away with the first significant conflict at Risdon in May 1804 just before Collins moved the settlement to Sullivan’s Cove. Once the Van Diemen’s Land Company was formed and began operations in the North West near Stanley in 1826, conflict with Aboriginal people escalated.

The biggest known massacre in Van Diemen’s Land was at Cape Grim near Stanley on lands of the Van Diemen’s Land Company in February 1828. Four shepherds are believed to have located a group of Aboriginal people. They shot 30 of them and threw their bodies off a 60 metre high cliff into the ocean. The massacre was retaliation for the killing of 118 sheep by the Aboriginal people. This in turn had been retaliation for the abduction of Aboriginal women by the shepherds (although some of this was undoubtedly undertaken by visiting whalers and sealers to the area). Trouble had begun as soon as the Company established grazing properties at Cape Grim in 1826. The magistrate of the area, Edward Curr, a manager of the Van Diemen’s Land Company, decided not to investigate the massacre and no charges were laid against the white shepherds. It was two years before another government official visited the area and he investigated the reports and concluded that 30 people had been massacred. By the time of the 1830 round up or “Black Line,” only 60 of the estimated 500 Aboriginal people living in the North West area in 1826 were still alive. This decline occurred from when the Van Diemen’s Land Company established itself in 1826 to 1830! But this terrible massacre is forgotten history, or is it? Apart from this known massacre there were frequent reprisals and shootings of Aboriginal people on the Van Diemen’s Land Company lands. In the Launceston area John Batman, who later went to Port Phillip Bay district, was very active in exterminating Aboriginals. For two years before 1830 he had led roving parties to track down men, women and children of the Ben Lomond tribe. His approach was to attack camps by surprise and kill all adult males and take the women and children as captives who he then handed over to government authorities for gaoling. Bateman was known for his violence against the boys he kept as his household servants.

In 1828 martial law against Aboriginal people in settled areas was proclaimed by Governor Arthur. The next step was the famous “Black Line” of 1830 whereby authorities tried to round up all Aboriginal people, not already in missions, by forming an impenetrable line. All able bodied men were to join a muster with one line beginning in Launceston and the other in Hobart with the idea that they would meet up in central regions and drive any Aboriginal people on to the Tasman Peninsula( Port Arthur) where they could be captured and shipped offshore. Some 2,200 men were involved – 1650 settlers and convicts and 500 soldiers in the 1830 March. It cost the astronomical figure of £30,000. George Robinson a lay missionary estimated there were only 50 Aboriginal people left in the central and eastern districts by 1830 but more on the west coast and north coasts. Consequently the Black Line was a dismal failure. Only two Aborigines were captured - one old man and a young boy. It was Arthur’s greatest failure as Governor of VDL. But between 1830 and 1835 roving parties, led by George Robertson of Bruny Island and a group of his trusted Aboriginal followers including Truganina, rounded up all Aboriginal people known from northern, western and eastern districts. They were firstly moved to Swan Island just off the north coast of Tasmania before being moved to Cape Barren Island and then Flinders Islands in Bass Strait. Aboriginal people then ended up at Wybalenna Station on Flinders Island with George Robinson as the Commandant. The authorities were determined to have no interference from Aboriginal Tasmanians on the mainland. But by 1836 George Robinson, who had tried valiantly to save Tasmanian Aboriginals from murderous white settlers, finally realised he had accelerated their extermination. Wybalenna was cold, wet and windy with limited natural food sources for the people to hunt in traditional ways. Diseases like influenza spread quickly among the last of the Tasmanian Aboriginals. Robinson had not provided a sanctuary for the Aboriginals but a graveyard for people pining their lost lands and lives. He then chose to leave Wybalenna in 1839 and cross Bass Strait to Port Phillip Bay district taking several Aboriginals with him including Truganina. Later Commandants inflicted or allowed serious abuse, especially of the women at Wybalenna, and with the dwindling number of residents, the rising rate of deaths and public criticisms, the government decided to close Wybalenna in 1847.

The last remaining Aborigines (47 in all) at Wybalenna were transferred to a new mission station at Oyster Cove near Kettering and Bruny Island. This was the final act in the subjugation of Tasmanian Aboriginals, following the loss of their hunting lands, the capture and enslavement of some of their women and the conflict and massacres. So within 50 years of settlement the Aboriginal population had dropped from between 4,000 and 10,000 to just 47. Apart from gun shots and violence, dislocation to Flinders Island, disease, and cultural destruction had almost destroyed an entire peoples. The last full blood Aboriginal to die was Truganini who died of old age and of bronchitis in a house in Hobart in 1876. In 2002 the massacre of the Tasmanian Aborigines re-emerged in the media and public arena. Keith Windschuttle in his book: “The Fabrication of Aboriginal History” claimed there was very little violence against Aborigines in Tasmania. Only 118 known Aboriginal deaths were ever recorded but around 190 whites were killed by Aboriginals between 1824 and 1831(hence the Black Line episode). Others claim about 700 were Aboriginals were killed by white colonists. Windschuttle (2002) believed most Aborigines died of disease. He argued that muskets were slow to reload so it is implausible that four shepherds at Cape Grim could shoot 30 fast running Aboriginal people. Several academics including Ian MacFarlane in his PhD and Josephine Flood in her book: “The Original Australians” have disputed Windschuttle’s claims. The history of massacres of Aboriginal people by British soldiers and the violence perpetrated by white farmers and escaped convicts had been overlooked by Windshuttle. The controversy has died down as detailed research has disproved some of his arguments but discovering the full truth of the numbers massacred so far back in the past is difficult. The truth is elusive.

Convict Settlement to Colony: 1803-1825.

Following Nicholas Baudin’s voyages and charting around SA and Van Diemen’s Land in 1802 Governor King got nervous about the intentions of France. So he despatched naval officer John Bowen to establish a convict settlement on the Derwent in 1803. He arrived there in September 1803. Meantime the British government had sent Captain Collins with a fleet and settlers to establish a new settlement on Port Phillip (where Sorrento is now located.) He arrived there in 1803. He decided the site was unsuitable and moved himself and his settlers on to the Derwent in January 1804. Governor King sent orders that Bowen was to hand over control of the settlement to Collins but Bowen tarried and did not do this until May 1804. Bowen left and returned to England at the end for that year and Collins became Lieutenant Governor. Hobart became the third settlement after Port Jackson, (1788), Norfolk Island (1790) and then Hobart (1803). Governor King was still worried about French intentions of colonising so he also sent Captain William Paterson to form a settlement on the Tamar at Port Dalrymple in November 1804. Thus began the settlement of Launceston in 1806 when Paterson moved his settlement to the better location of the junction of the South Esk and Tamar Rivers. Governor Macquarie interfered and had the settlement moved to George Town on Bass Strait. He relented in 1824 as he was about to leave NSW and Launceston was again founded!

The Van Diemen Land settlements began as convict outposts of NSW with the first shipments from NSW and then direct shipment of convicts from England to Hobart in 1812. But the British Colonial Office wanted to make money from these penal settlements so from 1813 the colony was open to international trade and commerce. Most convicts in DVL, as in NSW, were assigned to landowners to work for them or to government building teams. But in 1821 a major convict camp was opened in Macquarie Harbour on the West Coast for the most serious offenders. Conditions here were harsh, bleak because of the incessant rain and cold, and it was brutal. It was also a costly exercise to provision a penal settlement so far from a major port and from agricultural areas. Few convicts could escape as there was no other settlement on the west coast to escape to. Mainly because of its cost Macquarie Harbour penal settlement was closed in 1833 and these worst offenders moved to another isolated penal site surrounded by water on three sides- Port Arthur. The other early penal settlement on Maria Island which had opened in 1821 was closed at the same time in 1832 and its convicts moved to Port Arthur. The new largest penal community had begun in 1830 at Port Arthur. The 1820s saw some fairly rapid growth in Hobart and elsewhere. In 1821 Governor Macquarie of NSW visited VDL and personally named and selected sites for free townships at Perth, Campbell Town, Ross, Oatlands and Brighton thus opening up the central region between Hobart and Launceston.

Penal Colony to Self Government in Tasmania: 1825-1856.

This period began in 1825 with VDL being separated from NSW and becoming a colony in its own right. In that same year the Richmond Bridge, Australia’s oldest, was built in 1823 and opened to traffic. In 1826 the Van Diemans Land Company began its operations on the North West coast near Stanley. The period of the 1830s and 1840s saw VDL grow in population and settlement spread across the northern plains near Launceston, through the centre of the island, and around the Hobart area. It was a period when grand houses, fine churches and small villages were settled usually with much of their wealth coming from wool. Perhaps one sign of the maturing colony was the arrival of the first Anglican Bishop in 1843, the Rev. Francis Nixon who lived in Bishopsbourne, now called Runnymede in North Hobart. By then the Aborigines had been subdued but Bishop Nixon found plenty of missionary work necessary to improve living conditions for the Aborigines. This was also the period when libraries, hospitals, newspapers, sailing clubs and sport teams were established. In 1836 (the year when SA was founded) Governor Arthur, the first VDL Governor, left the colony to be the Governor of Upper Canada and by then the population had reached 43,000 of which 24,000 were “free” settlers. But most of these free settlers had been convicts at some stage and had been pardoned.

In 1849 the first anti-transportation (of convicts) meeting was held in Launceston. Shortly after this the British Colonial office announced that transportation to NSW, Queensland and Van Diemen’s Land (but not WA) would cease in 1853. The last convict ship from England arrived in Hobart in May 1853 (but convicts arrived from Norfolk Island in 1855). Partial self government was introduced in 1850 by the British Colonial Office. Full independence was not granted until 1856 when the colony’s name was change from Van Diemen’s Land to Tasmania. Later the name of the capital, Hobart Town, was changed to Hobart in 1881. But the convict heritage of Tasmania was not simply wiped away with the cessation of transportation in 1853. Convicts at Port Arthur were not released and the British did not withdraw its last militia forces from Port Arthur and Tasmania until 1870. Port Arthur finally closed as a prison in 1878 just a couple of years before the beautiful church at Port Arthur church was destroyed by fire. There were almost 900 prisoners at Port Arthur in 1863 including 100 who were serving life sentences. When it closed in 1878 it had 200 inmates (prisoners, convicts, paupers and lunatics.) But much of the convict built heritage of Tasmania has survived for us to see and admire today.

Richmond. The historic Courthouse built by convicts in 1825. Later became the Council Chambers. Date above main door.

Richmond, Old Hobart Town village and the Pooseum.

Just a short distance from Hobart is historic Richmond, home to Australia’s oldest bridge. The Coal River which flows through the town was named and discovered in 1803 not long after the Risdon Cove Hobart settlement began. Coal was discovered along the river banks hence the name. The government granted land to encourage farmers to the district and the town of Richmond was declared in 1824 by Lieutenant Governor William Sorrell. It was the gateway to the East Coast of VDL but also a police outpost with a Courthouse, Gaol, and barracks for soldiers and a watch house. An historic town like Richmond with buildings from the 1830s and 1840s is a testament to the role of convicts in building structures in Australia. Government work gangs of convicts built government and public structures such as the Richmond Bridge, the Courthouse, the Gaol etc but assigned convicts with skills would also have helped build some early structures including private houses for their masters. However, we have no records of this. The Richmond Bridge was built by convicts between 1823-25 and is still in daily use. Nearby is Australia’s oldest gaol built in 1825-28. The town grew quickly in the 1830s with much trade between it and Hobart. It is recorded that convicts built St Luke’s Anglican Church, (1834-36) a structure designed by architect John Lee Archer and opened by Governor Arthur. It is the church with the distinctive square tower and no spire. James Thompson the convict in charge of the interior wood work of the church was granted his freedom for his work. Note that the clock in St Luke’s tower came from the original St David’s church in Hobart when it was demolished in 1868 to make way for the Cathedral. The clock was made in 1828 and still keeps perfect time. The Catholic Church was not built by convicts as it was not the Anglican Church of the government. St John’s Catholic Church is the oldest Catholic Church in Australia and was built in 1836. The spire was added in the early 1900s. It also has an unusual side stone turret which houses the pre-cut stone stairs that give access to the gallery. The spire was added to St John’s in 1859 and was replaced again in 1972.

The heritage classified town has many fine Georgian buildings, antique shops and good cafes, 1830s cottages and grander houses. Look out for Oak Lodge in Bridge Street a gentleman’s two storey residence constructed between 1831-42. The bridge was used for all traffic to the east coast (and later to Port Arthur) and by 1830 Richmond was the third largest town in VDL. Wander down to the Coal River and walk under Richmond Bridge. The Richmond Court House was built in 1825-26 by convicts as was the Gaol nearby. Richmond Gaol was designed by Tasmanian architect John Lee Archer and erected by convicts as was the norm for government structures. The gaoler’s house was also designed by John Lee Archer. This complex is the oldest penal set up in Tasmania. In 1826 a group of Aborigines were believed to be attacking and raiding farms. Consequently a group of soldiers on a retribution search attacked and killed 14 Aboriginal people. Six were captured and taken to Richmond Gaol. They were subsequently released as there was no evidence that charges could be laid against them. Such victimisation was not uncommon in those days. Today Richmond relies on tourism and is the base for the Old Hobart Town model village and the scientific based Pooseum- the only one in the world established by an Austrian lady.

Some buildings to look for in Richmond starting in Bridge Street.

•On the corner of Henry St – Ashmore coffee shop. A two storey corner store circa 1850.

•LaFayette Galleries and shop – a fine Georgian style building. Built as a single storey Post Office c 1826. Opposite in old c1840 cottage is the Woodcraft Shop. And next to it is the stone Congregational Church built in 1873.

•The Regional Hotel – a typical 1880s Australian pub.

•On the corner of Edward St the old Saddlery. Originally a general store. Built around 1850.

•Next to it is the Bridge Inn licensed in 1834. Upper floor added in 1860s or so.

•Next to it is the Richmond Town Hall. Built in 1908 with stone from the flour mill and police barracks.

•Next to it is the Courthouse. Built by convicts in 1825. Used as Richmond Council Chambers 1861 to 1933.

•As the street bends on the north side is the old bakery c1830 now antiques shop and next to it some old cottages c1840.

•Opposite the cottages is Mill Cottage built around 1850.

•At the end of the street where the triangular park begins veer right to the Richmond Bridge 1823-25. You can walk down to the Coal River beneath the bridge.

•First over the bridge is Mill House as the water mill was on the river. Built in 1850. C1900 it became a butter factory.

•Turn left here into St Johns Court. It takes you to St John’s Catholic Church and spire.

Retrace your steps across the river and along Bridge Street to Edward St. by the old saddlery.

Edward Street.

•At the first intersection on the left is Ochil Cottage built c1840. Behind it down the side street is the Goal built 1825/28.

•Across the intersection the little cottage on left was a morgue and dispensary.

•Next left in Palladian style with a central two storey section is the Anglican Rectory. Built in 1831 for the town magistrate. Was only the Anglican Rectory 1908 to 1972.

•Next to it is St Luke’s Anglican Church built 1834/36. Built by convicts.

Retrace your steps to Bridge Street but detour right to 22 Bathurst St for a fine little cottage built circa 1830 with dormer windows. If you want to see more 1830s and 1840s houses walk down Commercial Street for one block only. It starts at the Ashmore coffee shop. Commercial St also has the Richmond Hotel, a fine Georgian two storey hotel built c1830.

Richmond. Hobart Town model miniature village from 1820s. The Commissariate store on Macquarie Street. Built in 1811 now the Tasmanian Museum and Gallery. .

54432958849_78335a453d_k

Richmond. The historic Courthouse built by convicts in 1825. Later became the Council Chambers.

Richmond, Old Hobart Town village and the Pooseum.

Just a short distance from Hobart is historic Richmond, home to Australia’s oldest bridge. The Coal River which flows through the town was named and discovered in 1803 not long after the Risdon Cove Hobart settlement began. Coal was discovered along the river banks hence the name. The government granted land to encourage farmers to the district and the town of Richmond was declared in 1824 by Lieutenant Governor William Sorrell. It was the gateway to the East Coast of VDL but also a police outpost with a Courthouse, Gaol, and barracks for soldiers and a watch house. An historic town like Richmond with buildings from the 1830s and 1840s is a testament to the role of convicts in building structures in Australia. Government work gangs of convicts built government and public structures such as the Richmond Bridge, the Courthouse, the Gaol etc but assigned convicts with skills would also have helped build some early structures including private houses for their masters. However, we have no records of this. The Richmond Bridge was built by convicts between 1823-25 and is still in daily use. Nearby is Australia’s oldest gaol built in 1825-28. The town grew quickly in the 1830s with much trade between it and Hobart. It is recorded that convicts built St Luke’s Anglican Church, (1834-36) a structure designed by architect John Lee Archer and opened by Governor Arthur. It is the church with the distinctive square tower and no spire. James Thompson the convict in charge of the interior wood work of the church was granted his freedom for his work. Note that the clock in St Luke’s tower came from the original St David’s church in Hobart when it was demolished in 1868 to make way for the Cathedral. The clock was made in 1828 and still keeps perfect time. The Catholic Church was not built by convicts as it was not the Anglican Church of the government. St John’s Catholic Church is the oldest Catholic Church in Australia and was built in 1836. The spire was added in the early 1900s. It also has an unusual side stone turret which houses the pre-cut stone stairs that give access to the gallery. The spire was added to St John’s in 1859 and was replaced again in 1972.

The heritage classified town has many fine Georgian buildings, antique shops and good cafes, 1830s cottages and grander houses. Look out for Oak Lodge in Bridge Street a gentleman’s two storey residence constructed between 1831-42. The bridge was used for all traffic to the east coast (and later to Port Arthur) and by 1830 Richmond was the third largest town in VDL. Wander down to the Coal River and walk under Richmond Bridge. The Richmond Court House was built in 1825-26 by convicts as was the Gaol nearby. Richmond Gaol was designed by Tasmanian architect John Lee Archer and erected by convicts as was the norm for government structures. The gaoler’s house was also designed by John Lee Archer. This complex is the oldest penal set up in Tasmania. In 1826 a group of Aborigines were believed to be attacking and raiding farms. Consequently a group of soldiers on a retribution search attacked and killed 14 Aboriginal people. Six were captured and taken to Richmond Gaol. They were subsequently released as there was no evidence that charges could be laid against them. Such victimisation was not uncommon in those days. Today Richmond relies on tourism and is the base for the Old Hobart Town model village and the scientific based Pooseum- the only one in the world established by an Austrian lady.

Some buildings to look for in Richmond starting in Bridge Street.

•On the corner of Henry St – Ashmore coffee shop. A two storey corner store circa 1850.

•LaFayette Galleries and shop – a fine Georgian style building. Built as a single storey Post Office c 1826. Opposite in old c1840 cottage is the Woodcraft Shop. And next to it is the stone Congregational Church built in 1873.

•The Regional Hotel – a typical 1880s Australian pub.

•On the corner of Edward St the old Saddlery. Originally a general store. Built around 1850.

•Next to it is the Bridge Inn licensed in 1834. Upper floor added in 1860s or so.

•Next to it is the Richmond Town Hall. Built in 1908 with stone from the flour mill and police barracks.

•Next to it is the Courthouse. Built by convicts in 1825. Used as Richmond Council Chambers 1861 to 1933.

•As the street bends on the north side is the old bakery c1830 now antiques shop and next to it some old cottages c1840.

•Opposite the cottages is Mill Cottage built around 1850.

•At the end of the street where the triangular park begins veer right to the Richmond Bridge 1823-25. You can walk down to the Coal River beneath the bridge.

•First over the bridge is Mill House as the water mill was on the river. Built in 1850. C1900 it became a butter factory.

•Turn left here into St Johns Court. It takes you to St John’s Catholic Church and spire.

Retrace your steps across the river and along Bridge Street to Edward St. by the old saddlery.

Edward Street.

•At the first intersection on the left is Ochil Cottage built c1840. Behind it down the side street is the Goal built 1825/28.

•Across the intersection the little cottage on left was a morgue and dispensary.

•Next left in Palladian style with a central two storey section is the Anglican Rectory. Built in 1831 for the town magistrate. Was only the Anglican Rectory 1908 to 1972.

•Next to it is St Luke’s Anglican Church built 1834/36. Built by convicts.

Retrace your steps to Bridge Street but detour right to 22 Bathurst St for a fine little cottage built circa 1830 with dormer windows. If you want to see more 1830s and 1840s houses walk down Commercial Street for one block only. It starts at the Ashmore coffee shop. Commercial St also has the Richmond Hotel, a fine Georgian two storey hotel built c1830.

Richmond. Hobart Town model miniature village from 1820s. The first St Davids Anglican Church on Macquarie Street. Built in 1817 - 24 and demolished. Site is now the Anglican Cathedral .

Overview of Tasmanian history. Early Exploration.

Abel Jansz Tasman of the Dutch East India Company discovered Tasmania in 1642 and named the island after Antony Diemen, Governor of the Dutch East India Company. Van Diemen’s Land was next sighted by the French Captain, du Fresne in 1772 just two years after Cook had sighted the east coast of Australia. Just 16 years later the British settled at Botany Bay and to deter further French exploration and possible settlement on Van Diemen’s Land they established an outpost of NSW on the island in the 1803. Prior to this, explorers like Captain Bligh in 1792 had sighted and named Mt Wellington and George Bass and Matthew Flinders circumnavigated the island in 1798. David Collins began the first island settlement in 1803 at Risdon, but moved it to Sullivan’s Cove in 1804(the wharf area of Hobart). Also in 1804, a northern settlement began at what is now George Town under the control of Colonel Paterson. Paterson moved this settlement to Launceston in 1806. In was not until 1812 that Governor Macquarie acted to bring all Van Diemen Land settlements under the control of Hobart Town. The settlements became semi-independent of NSW in 1825 when Van Diemen’s Land was allowed its own judiciary and Governor.

What happened to the Aborigines of Tasmania?

During the last Ice Age, New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania were joined as one land mass as sea levels were lower. During this cold period (about 35,000 years ago) Aborigines settled lowland parts of Tasmania. As the world warmed, sea levels dropped and about 12,000 years ago Aboriginal groups were left isolated on Tasmania. When whites began settlement of Tasmania there were 9 tribes on the island compromising between 4,000 and 10,000 Aboriginal people. Conflict between British settlers and military and the Aborigines began almost straight away with the first significant conflict at Risdon in May 1804 just before Collins moved the settlement to Sullivan’s Cove. Once the Van Diemen’s Land Company was formed and began operations in the North West near Stanley in 1826, conflict with Aboriginal people escalated.

The biggest known massacre in Van Diemen’s Land was at Cape Grim near Stanley on lands of the Van Diemen’s Land Company in February 1828. Four shepherds are believed to have located a group of Aboriginal people. They shot 30 of them and threw their bodies off a 60 metre high cliff into the ocean. The massacre was retaliation for the killing of 118 sheep by the Aboriginal people. This in turn had been retaliation for the abduction of Aboriginal women by the shepherds (although some of this was undoubtedly undertaken by visiting whalers and sealers to the area). Trouble had begun as soon as the Company established grazing properties at Cape Grim in 1826. The magistrate of the area, Edward Curr, a manager of the Van Diemen’s Land Company, decided not to investigate the massacre and no charges were laid against the white shepherds. It was two years before another government official visited the area and he investigated the reports and concluded that 30 people had been massacred. By the time of the 1830 round up or “Black Line,” only 60 of the estimated 500 Aboriginal people living in the North West area in 1826 were still alive. This decline occurred from when the Van Diemen’s Land Company established itself in 1826 to 1830! But this terrible massacre is forgotten history, or is it? Apart from this known massacre there were frequent reprisals and shootings of Aboriginal people on the Van Diemen’s Land Company lands. In the Launceston area John Batman, who later went to Port Phillip Bay district, was very active in exterminating Aboriginals. For two years before 1830 he had led roving parties to track down men, women and children of the Ben Lomond tribe. His approach was to attack camps by surprise and kill all adult males and take the women and children as captives who he then handed over to government authorities for gaoling. Bateman was known for his violence against the boys he kept as his household servants.

In 1828 martial law against Aboriginal people in settled areas was proclaimed by Governor Arthur. The next step was the famous “Black Line” of 1830 whereby authorities tried to round up all Aboriginal people, not already in missions, by forming an impenetrable line. All able bodied men were to join a muster with one line beginning in Launceston and the other in Hobart with the idea that they would meet up in central regions and drive any Aboriginal people on to the Tasman Peninsula( Port Arthur) where they could be captured and shipped offshore. Some 2,200 men were involved – 1650 settlers and convicts and 500 soldiers in the 1830 March. It cost the astronomical figure of £30,000. George Robinson a lay missionary estimated there were only 50 Aboriginal people left in the central and eastern districts by 1830 but more on the west coast and north coasts. Consequently the Black Line was a dismal failure. Only two Aborigines were captured - one old man and a young boy. It was Arthur’s greatest failure as Governor of VDL. But between 1830 and 1835 roving parties, led by George Robertson of Bruny Island and a group of his trusted Aboriginal followers including Truganina, rounded up all Aboriginal people known from northern, western and eastern districts. They were firstly moved to Swan Island just off the north coast of Tasmania before being moved to Cape Barren Island and then Flinders Islands in Bass Strait. Aboriginal people then ended up at Wybalenna Station on Flinders Island with George Robinson as the Commandant. The authorities were determined to have no interference from Aboriginal Tasmanians on the mainland. But by 1836 George Robinson, who had tried valiantly to save Tasmanian Aboriginals from murderous white settlers, finally realised he had accelerated their extermination. Wybalenna was cold, wet and windy with limited natural food sources for the people to hunt in traditional ways. Diseases like influenza spread quickly among the last of the Tasmanian Aboriginals. Robinson had not provided a sanctuary for the Aboriginals but a graveyard for people pining their lost lands and lives. He then chose to leave Wybalenna in 1839 and cross Bass Strait to Port Phillip Bay district taking several Aboriginals with him including Truganina. Later Commandants inflicted or allowed serious abuse, especially of the women at Wybalenna, and with the dwindling number of residents, the rising rate of deaths and public criticisms, the government decided to close Wybalenna in 1847.

The last remaining Aborigines (47 in all) at Wybalenna were transferred to a new mission station at Oyster Cove near Kettering and Bruny Island. This was the final act in the subjugation of Tasmanian Aboriginals, following the loss of their hunting lands, the capture and enslavement of some of their women and the conflict and massacres. So within 50 years of settlement the Aboriginal population had dropped from between 4,000 and 10,000 to just 47. Apart from gun shots and violence, dislocation to Flinders Island, disease, and cultural destruction had almost destroyed an entire peoples. The last full blood Aboriginal to die was Truganini who died of old age and of bronchitis in a house in Hobart in 1876. In 2002 the massacre of the Tasmanian Aborigines re-emerged in the media and public arena. Keith Windschuttle in his book: “The Fabrication of Aboriginal History” claimed there was very little violence against Aborigines in Tasmania. Only 118 known Aboriginal deaths were ever recorded but around 190 whites were killed by Aboriginals between 1824 and 1831(hence the Black Line episode). Others claim about 700 were Aboriginals were killed by white colonists. Windschuttle (2002) believed most Aborigines died of disease. He argued that muskets were slow to reload so it is implausible that four shepherds at Cape Grim could shoot 30 fast running Aboriginal people. Several academics including Ian MacFarlane in his PhD and Josephine Flood in her book: “The Original Australians” have disputed Windschuttle’s claims. The history of massacres of Aboriginal people by British soldiers and the violence perpetrated by white farmers and escaped convicts had been overlooked by Windshuttle. The controversy has died down as detailed research has disproved some of his arguments but discovering the full truth of the numbers massacred so far back in the past is difficult. The truth is elusive.

Convict Settlement to Colony: 1803-1825.

Following Nicholas Baudin’s voyages and charting around SA and Van Diemen’s Land in 1802 Governor King got nervous about the intentions of France. So he despatched naval officer John Bowen to establish a convict settlement on the Derwent in 1803. He arrived there in September 1803. Meantime the British government had sent Captain Collins with a fleet and settlers to establish a new settlement on Port Phillip (where Sorrento is now located.) He arrived there in 1803. He decided the site was unsuitable and moved himself and his settlers on to the Derwent in January 1804. Governor King sent orders that Bowen was to hand over control of the settlement to Collins but Bowen tarried and did not do this until May 1804. Bowen left and returned to England at the end for that year and Collins became Lieutenant Governor. Hobart became the third settlement after Port Jackson, (1788), Norfolk Island (1790) and then Hobart (1803). Governor King was still worried about French intentions of colonising so he also sent Captain William Paterson to form a settlement on the Tamar at Port Dalrymple in November 1804. Thus began the settlement of Launceston in 1806 when Paterson moved his settlement to the better location of the junction of the South Esk and Tamar Rivers. Governor Macquarie interfered and had the settlement moved to George Town on Bass Strait. He relented in 1824 as he was about to leave NSW and Launceston was again founded!

The Van Diemen Land settlements began as convict outposts of NSW with the first shipments from NSW and then direct shipment of convicts from England to Hobart in 1812. But the British Colonial Office wanted to make money from these penal settlements so from 1813 the colony was open to international trade and commerce. Most convicts in DVL, as in NSW, were assigned to landowners to work for them or to government building teams. But in 1821 a major convict camp was opened in Macquarie Harbour on the West Coast for the most serious offenders. Conditions here were harsh, bleak because of the incessant rain and cold, and it was brutal. It was also a costly exercise to provision a penal settlement so far from a major port and from agricultural areas. Few convicts could escape as there was no other settlement on the west coast to escape to. Mainly because of its cost Macquarie Harbour penal settlement was closed in 1833 and these worst offenders moved to another isolated penal site surrounded by water on three sides- Port Arthur. The other early penal settlement on Maria Island which had opened in 1821 was closed at the same time in 1832 and its convicts moved to Port Arthur. The new largest penal community had begun in 1830 at Port Arthur. The 1820s saw some fairly rapid growth in Hobart and elsewhere. In 1821 Governor Macquarie of NSW visited VDL and personally named and selected sites for free townships at Perth, Campbell Town, Ross, Oatlands and Brighton thus opening up the central region between Hobart and Launceston.

Penal Colony to Self Government in Tasmania: 1825-1856.

This period began in 1825 with VDL being separated from NSW and becoming a colony in its own right. In that same year the Richmond Bridge, Australia’s oldest, was built in 1823 and opened to traffic. In 1826 the Van Diemans Land Company began its operations on the North West coast near Stanley. The period of the 1830s and 1840s saw VDL grow in population and settlement spread across the northern plains near Launceston, through the centre of the island, and around the Hobart area. It was a period when grand houses, fine churches and small villages were settled usually with much of their wealth coming from wool. Perhaps one sign of the maturing colony was the arrival of the first Anglican Bishop in 1843, the Rev. Francis Nixon who lived in Bishopsbourne, now called Runnymede in North Hobart. By then the Aborigines had been subdued but Bishop Nixon found plenty of missionary work necessary to improve living conditions for the Aborigines. This was also the period when libraries, hospitals, newspapers, sailing clubs and sport teams were established. In 1836 (the year when SA was founded) Governor Arthur, the first VDL Governor, left the colony to be the Governor of Upper Canada and by then the population had reached 43,000 of which 24,000 were “free” settlers. But most of these free settlers had been convicts at some stage and had been pardoned.

In 1849 the first anti-transportation (of convicts) meeting was held in Launceston. Shortly after this the British Colonial office announced that transportation to NSW, Queensland and Van Diemen’s Land (but not WA) would cease in 1853. The last convict ship from England arrived in Hobart in May 1853 (but convicts arrived from Norfolk Island in 1855). Partial self government was introduced in 1850 by the British Colonial Office. Full independence was not granted until 1856 when the colony’s name was change from Van Diemen’s Land to Tasmania. Later the name of the capital, Hobart Town, was changed to Hobart in 1881. But the convict heritage of Tasmania was not simply wiped away with the cessation of transportation in 1853. Convicts at Port Arthur were not released and the British did not withdraw its last militia forces from Port Arthur and Tasmania until 1870. Port Arthur finally closed as a prison in 1878 just a couple of years before the beautiful church at Port Arthur church was destroyed by fire. There were almost 900 prisoners at Port Arthur in 1863 including 100 who were serving life sentences. When it closed in 1878 it had 200 inmates (prisoners, convicts, paupers and lunatics.) But much of the convict built heritage of Tasmania has survived for us to see and admire today.

Richmond. Hobart Town model miniature village from 1820s. Warehouse on Hunter Island which is now Hunter Street.

Overview of Tasmanian history. Early Exploration.

Abel Jansz Tasman of the Dutch East India Company discovered Tasmania in 1642 and named the island after Antony Diemen, Governor of the Dutch East India Company. Van Diemen’s Land was next sighted by the French Captain, du Fresne in 1772 just two years after Cook had sighted the east coast of Australia. Just 16 years later the British settled at Botany Bay and to deter further French exploration and possible settlement on Van Diemen’s Land they established an outpost of NSW on the island in the 1803. Prior to this, explorers like Captain Bligh in 1792 had sighted and named Mt Wellington and George Bass and Matthew Flinders circumnavigated the island in 1798. David Collins began the first island settlement in 1803 at Risdon, but moved it to Sullivan’s Cove in 1804(the wharf area of Hobart). Also in 1804, a northern settlement began at what is now George Town under the control of Colonel Paterson. Paterson moved this settlement to Launceston in 1806. In was not until 1812 that Governor Macquarie acted to bring all Van Diemen Land settlements under the control of Hobart Town. The settlements became semi-independent of NSW in 1825 when Van Diemen’s Land was allowed its own judiciary and Governor.

What happened to the Aborigines of Tasmania?

During the last Ice Age, New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania were joined as one land mass as sea levels were lower. During this cold period (about 35,000 years ago) Aborigines settled lowland parts of Tasmania. As the world warmed, sea levels dropped and about 12,000 years ago Aboriginal groups were left isolated on Tasmania. When whites began settlement of Tasmania there were 9 tribes on the island compromising between 4,000 and 10,000 Aboriginal people. Conflict between British settlers and military and the Aborigines began almost straight away with the first significant conflict at Risdon in May 1804 just before Collins moved the settlement to Sullivan’s Cove. Once the Van Diemen’s Land Company was formed and began operations in the North West near Stanley in 1826, conflict with Aboriginal people escalated.

The biggest known massacre in Van Diemen’s Land was at Cape Grim near Stanley on lands of the Van Diemen’s Land Company in February 1828. Four shepherds are believed to have located a group of Aboriginal people. They shot 30 of them and threw their bodies off a 60 metre high cliff into the ocean. The massacre was retaliation for the killing of 118 sheep by the Aboriginal people. This in turn had been retaliation for the abduction of Aboriginal women by the shepherds (although some of this was undoubtedly undertaken by visiting whalers and sealers to the area). Trouble had begun as soon as the Company established grazing properties at Cape Grim in 1826. The magistrate of the area, Edward Curr, a manager of the Van Diemen’s Land Company, decided not to investigate the massacre and no charges were laid against the white shepherds. It was two years before another government official visited the area and he investigated the reports and concluded that 30 people had been massacred. By the time of the 1830 round up or “Black Line,” only 60 of the estimated 500 Aboriginal people living in the North West area in 1826 were still alive. This decline occurred from when the Van Diemen’s Land Company established itself in 1826 to 1830! But this terrible massacre is forgotten history, or is it? Apart from this known massacre there were frequent reprisals and shootings of Aboriginal people on the Van Diemen’s Land Company lands. In the Launceston area John Batman, who later went to Port Phillip Bay district, was very active in exterminating Aboriginals. For two years before 1830 he had led roving parties to track down men, women and children of the Ben Lomond tribe. His approach was to attack camps by surprise and kill all adult males and take the women and children as captives who he then handed over to government authorities for gaoling. Bateman was known for his violence against the boys he kept as his household servants.

In 1828 martial law against Aboriginal people in settled areas was proclaimed by Governor Arthur. The next step was the famous “Black Line” of 1830 whereby authorities tried to round up all Aboriginal people, not already in missions, by forming an impenetrable line. All able bodied men were to join a muster with one line beginning in Launceston and the other in Hobart with the idea that they would meet up in central regions and drive any Aboriginal people on to the Tasman Peninsula( Port Arthur) where they could be captured and shipped offshore. Some 2,200 men were involved – 1650 settlers and convicts and 500 soldiers in the 1830 March. It cost the astronomical figure of £30,000. George Robinson a lay missionary estimated there were only 50 Aboriginal people left in the central and eastern districts by 1830 but more on the west coast and north coasts. Consequently the Black Line was a dismal failure. Only two Aborigines were captured - one old man and a young boy. It was Arthur’s greatest failure as Governor of VDL. But between 1830 and 1835 roving parties, led by George Robertson of Bruny Island and a group of his trusted Aboriginal followers including Truganina, rounded up all Aboriginal people known from northern, western and eastern districts. They were firstly moved to Swan Island just off the north coast of Tasmania before being moved to Cape Barren Island and then Flinders Islands in Bass Strait. Aboriginal people then ended up at Wybalenna Station on Flinders Island with George Robinson as the Commandant. The authorities were determined to have no interference from Aboriginal Tasmanians on the mainland. But by 1836 George Robinson, who had tried valiantly to save Tasmanian Aboriginals from murderous white settlers, finally realised he had accelerated their extermination. Wybalenna was cold, wet and windy with limited natural food sources for the people to hunt in traditional ways. Diseases like influenza spread quickly among the last of the Tasmanian Aboriginals. Robinson had not provided a sanctuary for the Aboriginals but a graveyard for people pining their lost lands and lives. He then chose to leave Wybalenna in 1839 and cross Bass Strait to Port Phillip Bay district taking several Aboriginals with him including Truganina. Later Commandants inflicted or allowed serious abuse, especially of the women at Wybalenna, and with the dwindling number of residents, the rising rate of deaths and public criticisms, the government decided to close Wybalenna in 1847.

The last remaining Aborigines (47 in all) at Wybalenna were transferred to a new mission station at Oyster Cove near Kettering and Bruny Island. This was the final act in the subjugation of Tasmanian Aboriginals, following the loss of their hunting lands, the capture and enslavement of some of their women and the conflict and massacres. So within 50 years of settlement the Aboriginal population had dropped from between 4,000 and 10,000 to just 47. Apart from gun shots and violence, dislocation to Flinders Island, disease, and cultural destruction had almost destroyed an entire peoples. The last full blood Aboriginal to die was Truganini who died of old age and of bronchitis in a house in Hobart in 1876. In 2002 the massacre of the Tasmanian Aborigines re-emerged in the media and public arena. Keith Windschuttle in his book: “The Fabrication of Aboriginal History” claimed there was very little violence against Aborigines in Tasmania. Only 118 known Aboriginal deaths were ever recorded but around 190 whites were killed by Aboriginals between 1824 and 1831(hence the Black Line episode). Others claim about 700 were Aboriginals were killed by white colonists. Windschuttle (2002) believed most Aborigines died of disease. He argued that muskets were slow to reload so it is implausible that four shepherds at Cape Grim could shoot 30 fast running Aboriginal people. Several academics including Ian MacFarlane in his PhD and Josephine Flood in her book: “The Original Australians” have disputed Windschuttle’s claims. The history of massacres of Aboriginal people by British soldiers and the violence perpetrated by white farmers and escaped convicts had been overlooked by Windshuttle. The controversy has died down as detailed research has disproved some of his arguments but discovering the full truth of the numbers massacred so far back in the past is difficult. The truth is elusive.

Convict Settlement to Colony: 1803-1825.

Following Nicholas Baudin’s voyages and charting around SA and Van Diemen’s Land in 1802 Governor King got nervous about the intentions of France. So he despatched naval officer John Bowen to establish a convict settlement on the Derwent in 1803. He arrived there in September 1803. Meantime the British government had sent Captain Collins with a fleet and settlers to establish a new settlement on Port Phillip (where Sorrento is now located.) He arrived there in 1803. He decided the site was unsuitable and moved himself and his settlers on to the Derwent in January 1804. Governor King sent orders that Bowen was to hand over control of the settlement to Collins but Bowen tarried and did not do this until May 1804. Bowen left and returned to England at the end for that year and Collins became Lieutenant Governor. Hobart became the third settlement after Port Jackson, (1788), Norfolk Island (1790) and then Hobart (1803). Governor King was still worried about French intentions of colonising so he also sent Captain William Paterson to form a settlement on the Tamar at Port Dalrymple in November 1804. Thus began the settlement of Launceston in 1806 when Paterson moved his settlement to the better location of the junction of the South Esk and Tamar Rivers. Governor Macquarie interfered and had the settlement moved to George Town on Bass Strait. He relented in 1824 as he was about to leave NSW and Launceston was again founded!

The Van Diemen Land settlements began as convict outposts of NSW with the first shipments from NSW and then direct shipment of convicts from England to Hobart in 1812. But the British Colonial Office wanted to make money from these penal settlements so from 1813 the colony was open to international trade and commerce. Most convicts in DVL, as in NSW, were assigned to landowners to work for them or to government building teams. But in 1821 a major convict camp was opened in Macquarie Harbour on the West Coast for the most serious offenders. Conditions here were harsh, bleak because of the incessant rain and cold, and it was brutal. It was also a costly exercise to provision a penal settlement so far from a major port and from agricultural areas. Few convicts could escape as there was no other settlement on the west coast to escape to. Mainly because of its cost Macquarie Harbour penal settlement was closed in 1833 and these worst offenders moved to another isolated penal site surrounded by water on three sides- Port Arthur. The other early penal settlement on Maria Island which had opened in 1821 was closed at the same time in 1832 and its convicts moved to Port Arthur. The new largest penal community had begun in 1830 at Port Arthur. The 1820s saw some fairly rapid growth in Hobart and elsewhere. In 1821 Governor Macquarie of NSW visited VDL and personally named and selected sites for free townships at Perth, Campbell Town, Ross, Oatlands and Brighton thus opening up the central region between Hobart and Launceston.

Penal Colony to Self Government in Tasmania: 1825-1856.

This period began in 1825 with VDL being separated from NSW and becoming a colony in its own right. In that same year the Richmond Bridge, Australia’s oldest, was built in 1823 and opened to traffic. In 1826 the Van Diemans Land Company began its operations on the North West coast near Stanley. The period of the 1830s and 1840s saw VDL grow in population and settlement spread across the northern plains near Launceston, through the centre of the island, and around the Hobart area. It was a period when grand houses, fine churches and small villages were settled usually with much of their wealth coming from wool. Perhaps one sign of the maturing colony was the arrival of the first Anglican Bishop in 1843, the Rev. Francis Nixon who lived in Bishopsbourne, now called Runnymede in North Hobart. By then the Aborigines had been subdued but Bishop Nixon found plenty of missionary work necessary to improve living conditions for the Aborigines. This was also the period when libraries, hospitals, newspapers, sailing clubs and sport teams were established. In 1836 (the year when SA was founded) Governor Arthur, the first VDL Governor, left the colony to be the Governor of Upper Canada and by then the population had reached 43,000 of which 24,000 were “free” settlers. But most of these free settlers had been convicts at some stage and had been pardoned.

In 1849 the first anti-transportation (of convicts) meeting was held in Launceston. Shortly after this the British Colonial office announced that transportation to NSW, Queensland and Van Diemen’s Land (but not WA) would cease in 1853. The last convict ship from England arrived in Hobart in May 1853 (but convicts arrived from Norfolk Island in 1855). Partial self government was introduced in 1850 by the British Colonial Office. Full independence was not granted until 1856 when the colony’s name was change from Van Diemen’s Land to Tasmania. Later the name of the capital, Hobart Town, was changed to Hobart in 1881. But the convict heritage of Tasmania was not simply wiped away with the cessation of transportation in 1853. Convicts at Port Arthur were not released and the British did not withdraw its last militia forces from Port Arthur and Tasmania until 1870. Port Arthur finally closed as a prison in 1878 just a couple of years before the beautiful church at Port Arthur church was destroyed by fire. There were almost 900 prisoners at Port Arthur in 1863 including 100 who were serving life sentences. When it closed in 1878 it had 200 inmates (prisoners, convicts, paupers and lunatics.) But much of the convict built heritage of Tasmania has survived for us to see and admire today.

Richmond. Hobart Town model miniature village from 1820s. The first St Davids Anglican Church on Macquarie Street. Built in 1817 - 24 and demolished in 1874. Site is now the Anglican Cathedral .

Overview of Tasmanian history. Early Exploration.

Abel Jansz Tasman of the Dutch East India Company discovered Tasmania in 1642 and named the island after Antony Diemen, Governor of the Dutch East India Company. Van Diemen’s Land was next sighted by the French Captain, du Fresne in 1772 just two years after Cook had sighted the east coast of Australia. Just 16 years later the British settled at Botany Bay and to deter further French exploration and possible settlement on Van Diemen’s Land they established an outpost of NSW on the island in the 1803. Prior to this, explorers like Captain Bligh in 1792 had sighted and named Mt Wellington and George Bass and Matthew Flinders circumnavigated the island in 1798. David Collins began the first island settlement in 1803 at Risdon, but moved it to Sullivan’s Cove in 1804(the wharf area of Hobart). Also in 1804, a northern settlement began at what is now George Town under the control of Colonel Paterson. Paterson moved this settlement to Launceston in 1806. In was not until 1812 that Governor Macquarie acted to bring all Van Diemen Land settlements under the control of Hobart Town. The settlements became semi-independent of NSW in 1825 when Van Diemen’s Land was allowed its own judiciary and Governor.

What happened to the Aborigines of Tasmania?

During the last Ice Age, New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania were joined as one land mass as sea levels were lower. During this cold period (about 35,000 years ago) Aborigines settled lowland parts of Tasmania. As the world warmed, sea levels dropped and about 12,000 years ago Aboriginal groups were left isolated on Tasmania. When whites began settlement of Tasmania there were 9 tribes on the island compromising between 4,000 and 10,000 Aboriginal people. Conflict between British settlers and military and the Aborigines began almost straight away with the first significant conflict at Risdon in May 1804 just before Collins moved the settlement to Sullivan’s Cove. Once the Van Diemen’s Land Company was formed and began operations in the North West near Stanley in 1826, conflict with Aboriginal people escalated.

The biggest known massacre in Van Diemen’s Land was at Cape Grim near Stanley on lands of the Van Diemen’s Land Company in February 1828. Four shepherds are believed to have located a group of Aboriginal people. They shot 30 of them and threw their bodies off a 60 metre high cliff into the ocean. The massacre was retaliation for the killing of 118 sheep by the Aboriginal people. This in turn had been retaliation for the abduction of Aboriginal women by the shepherds (although some of this was undoubtedly undertaken by visiting whalers and sealers to the area). Trouble had begun as soon as the Company established grazing properties at Cape Grim in 1826. The magistrate of the area, Edward Curr, a manager of the Van Diemen’s Land Company, decided not to investigate the massacre and no charges were laid against the white shepherds. It was two years before another government official visited the area and he investigated the reports and concluded that 30 people had been massacred. By the time of the 1830 round up or “Black Line,” only 60 of the estimated 500 Aboriginal people living in the North West area in 1826 were still alive. This decline occurred from when the Van Diemen’s Land Company established itself in 1826 to 1830! But this terrible massacre is forgotten history, or is it? Apart from this known massacre there were frequent reprisals and shootings of Aboriginal people on the Van Diemen’s Land Company lands. In the Launceston area John Batman, who later went to Port Phillip Bay district, was very active in exterminating Aboriginals. For two years before 1830 he had led roving parties to track down men, women and children of the Ben Lomond tribe. His approach was to attack camps by surprise and kill all adult males and take the women and children as captives who he then handed over to government authorities for gaoling. Bateman was known for his violence against the boys he kept as his household servants.

In 1828 martial law against Aboriginal people in settled areas was proclaimed by Governor Arthur. The next step was the famous “Black Line” of 1830 whereby authorities tried to round up all Aboriginal people, not already in missions, by forming an impenetrable line. All able bodied men were to join a muster with one line beginning in Launceston and the other in Hobart with the idea that they would meet up in central regions and drive any Aboriginal people on to the Tasman Peninsula( Port Arthur) where they could be captured and shipped offshore. Some 2,200 men were involved – 1650 settlers and convicts and 500 soldiers in the 1830 March. It cost the astronomical figure of £30,000. George Robinson a lay missionary estimated there were only 50 Aboriginal people left in the central and eastern districts by 1830 but more on the west coast and north coasts. Consequently the Black Line was a dismal failure. Only two Aborigines were captured - one old man and a young boy. It was Arthur’s greatest failure as Governor of VDL. But between 1830 and 1835 roving parties, led by George Robertson of Bruny Island and a group of his trusted Aboriginal followers including Truganina, rounded up all Aboriginal people known from northern, western and eastern districts. They were firstly moved to Swan Island just off the north coast of Tasmania before being moved to Cape Barren Island and then Flinders Islands in Bass Strait. Aboriginal people then ended up at Wybalenna Station on Flinders Island with George Robinson as the Commandant. The authorities were determined to have no interference from Aboriginal Tasmanians on the mainland. But by 1836 George Robinson, who had tried valiantly to save Tasmanian Aboriginals from murderous white settlers, finally realised he had accelerated their extermination. Wybalenna was cold, wet and windy with limited natural food sources for the people to hunt in traditional ways. Diseases like influenza spread quickly among the last of the Tasmanian Aboriginals. Robinson had not provided a sanctuary for the Aboriginals but a graveyard for people pining their lost lands and lives. He then chose to leave Wybalenna in 1839 and cross Bass Strait to Port Phillip Bay district taking several Aboriginals with him including Truganina. Later Commandants inflicted or allowed serious abuse, especially of the women at Wybalenna, and with the dwindling number of residents, the rising rate of deaths and public criticisms, the government decided to close Wybalenna in 1847.

The last remaining Aborigines (47 in all) at Wybalenna were transferred to a new mission station at Oyster Cove near Kettering and Bruny Island. This was the final act in the subjugation of Tasmanian Aboriginals, following the loss of their hunting lands, the capture and enslavement of some of their women and the conflict and massacres. So within 50 years of settlement the Aboriginal population had dropped from between 4,000 and 10,000 to just 47. Apart from gun shots and violence, dislocation to Flinders Island, disease, and cultural destruction had almost destroyed an entire peoples. The last full blood Aboriginal to die was Truganini who died of old age and of bronchitis in a house in Hobart in 1876. In 2002 the massacre of the Tasmanian Aborigines re-emerged in the media and public arena. Keith Windschuttle in his book: “The Fabrication of Aboriginal History” claimed there was very little violence against Aborigines in Tasmania. Only 118 known Aboriginal deaths were ever recorded but around 190 whites were killed by Aboriginals between 1824 and 1831(hence the Black Line episode). Others claim about 700 were Aboriginals were killed by white colonists. Windschuttle (2002) believed most Aborigines died of disease. He argued that muskets were slow to reload so it is implausible that four shepherds at Cape Grim could shoot 30 fast running Aboriginal people. Several academics including Ian MacFarlane in his PhD and Josephine Flood in her book: “The Original Australians” have disputed Windschuttle’s claims. The history of massacres of Aboriginal people by British soldiers and the violence perpetrated by white farmers and escaped convicts had been overlooked by Windshuttle. The controversy has died down as detailed research has disproved some of his arguments but discovering the full truth of the numbers massacred so far back in the past is difficult. The truth is elusive.

Convict Settlement to Colony: 1803-1825.

Following Nicholas Baudin’s voyages and charting around SA and Van Diemen’s Land in 1802 Governor King got nervous about the intentions of France. So he despatched naval officer John Bowen to establish a convict settlement on the Derwent in 1803. He arrived there in September 1803. Meantime the British government had sent Captain Collins with a fleet and settlers to establish a new settlement on Port Phillip (where Sorrento is now located.) He arrived there in 1803. He decided the site was unsuitable and moved himself and his settlers on to the Derwent in January 1804. Governor King sent orders that Bowen was to hand over control of the settlement to Collins but Bowen tarried and did not do this until May 1804. Bowen left and returned to England at the end for that year and Collins became Lieutenant Governor. Hobart became the third settlement after Port Jackson, (1788), Norfolk Island (1790) and then Hobart (1803). Governor King was still worried about French intentions of colonising so he also sent Captain William Paterson to form a settlement on the Tamar at Port Dalrymple in November 1804. Thus began the settlement of Launceston in 1806 when Paterson moved his settlement to the better location of the junction of the South Esk and Tamar Rivers. Governor Macquarie interfered and had the settlement moved to George Town on Bass Strait. He relented in 1824 as he was about to leave NSW and Launceston was again founded!

The Van Diemen Land settlements began as convict outposts of NSW with the first shipments from NSW and then direct shipment of convicts from England to Hobart in 1812. But the British Colonial Office wanted to make money from these penal settlements so from 1813 the colony was open to international trade and commerce. Most convicts in DVL, as in NSW, were assigned to landowners to work for them or to government building teams. But in 1821 a major convict camp was opened in Macquarie Harbour on the West Coast for the most serious offenders. Conditions here were harsh, bleak because of the incessant rain and cold, and it was brutal. It was also a costly exercise to provision a penal settlement so far from a major port and from agricultural areas. Few convicts could escape as there was no other settlement on the west coast to escape to. Mainly because of its cost Macquarie Harbour penal settlement was closed in 1833 and these worst offenders moved to another isolated penal site surrounded by water on three sides- Port Arthur. The other early penal settlement on Maria Island which had opened in 1821 was closed at the same time in 1832 and its convicts moved to Port Arthur. The new largest penal community had begun in 1830 at Port Arthur. The 1820s saw some fairly rapid growth in Hobart and elsewhere. In 1821 Governor Macquarie of NSW visited VDL and personally named and selected sites for free townships at Perth, Campbell Town, Ross, Oatlands and Brighton thus opening up the central region between Hobart and Launceston.

Penal Colony to Self Government in Tasmania: 1825-1856.

This period began in 1825 with VDL being separated from NSW and becoming a colony in its own right. In that same year the Richmond Bridge, Australia’s oldest, was built in 1823 and opened to traffic. In 1826 the Van Diemans Land Company began its operations on the North West coast near Stanley. The period of the 1830s and 1840s saw VDL grow in population and settlement spread across the northern plains near Launceston, through the centre of the island, and around the Hobart area. It was a period when grand houses, fine churches and small villages were settled usually with much of their wealth coming from wool. Perhaps one sign of the maturing colony was the arrival of the first Anglican Bishop in 1843, the Rev. Francis Nixon who lived in Bishopsbourne, now called Runnymede in North Hobart. By then the Aborigines had been subdued but Bishop Nixon found plenty of missionary work necessary to improve living conditions for the Aborigines. This was also the period when libraries, hospitals, newspapers, sailing clubs and sport teams were established. In 1836 (the year when SA was founded) Governor Arthur, the first VDL Governor, left the colony to be the Governor of Upper Canada and by then the population had reached 43,000 of which 24,000 were “free” settlers. But most of these free settlers had been convicts at some stage and had been pardoned.

In 1849 the first anti-transportation (of convicts) meeting was held in Launceston. Shortly after this the British Colonial office announced that transportation to NSW, Queensland and Van Diemen’s Land (but not WA) would cease in 1853. The last convict ship from England arrived in Hobart in May 1853 (but convicts arrived from Norfolk Island in 1855). Partial self government was introduced in 1850 by the British Colonial Office. Full independence was not granted until 1856 when the colony’s name was change from Van Diemen’s Land to Tasmania. Later the name of the capital, Hobart Town, was changed to Hobart in 1881. But the convict heritage of Tasmania was not simply wiped away with the cessation of transportation in 1853. Convicts at Port Arthur were not released and the British did not withdraw its last militia forces from Port Arthur and Tasmania until 1870. Port Arthur finally closed as a prison in 1878 just a couple of years before the beautiful church at Port Arthur church was destroyed by fire. There were almost 900 prisoners at Port Arthur in 1863 including 100 who were serving life sentences. When it closed in 1878 it had 200 inmates (prisoners, convicts, paupers and lunatics.) But much of the convict built heritage of Tasmania has survived for us to see and admire today.

Richmond. Hobart Town model miniature village from 1820s. The second Government House on Macquarie Street. Built in 1817 and demolished in 1858. Site is now Franklin Square. .

Overview of Tasmanian history. Early Exploration.

Abel Jansz Tasman of the Dutch East India Company discovered Tasmania in 1642 and named the island after Antony Diemen, Governor of the Dutch East India Company. Van Diemen’s Land was next sighted by the French Captain, du Fresne in 1772 just two years after Cook had sighted the east coast of Australia. Just 16 years later the British settled at Botany Bay and to deter further French exploration and possible settlement on Van Diemen’s Land they established an outpost of NSW on the island in the 1803. Prior to this, explorers like Captain Bligh in 1792 had sighted and named Mt Wellington and George Bass and Matthew Flinders circumnavigated the island in 1798. David Collins began the first island settlement in 1803 at Risdon, but moved it to Sullivan’s Cove in 1804(the wharf area of Hobart). Also in 1804, a northern settlement began at what is now George Town under the control of Colonel Paterson. Paterson moved this settlement to Launceston in 1806. In was not until 1812 that Governor Macquarie acted to bring all Van Diemen Land settlements under the control of Hobart Town. The settlements became semi-independent of NSW in 1825 when Van Diemen’s Land was allowed its own judiciary and Governor.

What happened to the Aborigines of Tasmania?

During the last Ice Age, New Guinea, Australia and Tasmania were joined as one land mass as sea levels were lower. During this cold period (about 35,000 years ago) Aborigines settled lowland parts of Tasmania. As the world warmed, sea levels dropped and about 12,000 years ago Aboriginal groups were left isolated on Tasmania. When whites began settlement of Tasmania there were 9 tribes on the island compromising between 4,000 and 10,000 Aboriginal people. Conflict between British settlers and military and the Aborigines began almost straight away with the first significant conflict at Risdon in May 1804 just before Collins moved the settlement to Sullivan’s Cove. Once the Van Diemen’s Land Company was formed and began operations in the North West near Stanley in 1826, conflict with Aboriginal people escalated.